Honore Daumier (1808-1879) was a French caricaturist, sculptor, graphic artist and painter, whose thousands of satirical lithographs created an unforgettable record of the ironies of human behaviour. best known in his life time as a graphic artist and political and social satirist. His paintings, best known since his death, are an important link in the development of modern art. His bold, dramatic paintings were largely devoted to everyday themes and contained a strong note of social protest. He produced nearly 4000 lithographs and his prints had a wider public than many modern artists. He was thus an illustrator and deeply human caricaturist, who understood the psychological implications of his political and social subjects.

Honore Daumier was the son of a glassmaker. born in Marseille on either the 20th or 26th of February, 1808, and as a boy moved to Paris with his family. In Paris he worked in various capacities as a bookseller’s assistant messenger in the law courts. His real enthusiasm was reserved for drawing and politics. He studied drawing with Alexandre Lenoir and at the Academie Suisse, and then as an assistant to the lithographer Beliard. An association with the director of the Musee des Monuments de France gave him an interest in sculpture which affected his whole career. He began his career by making drawings for advertisements. Honore lived with his seamstress wife in Paris. Daumier was 22 when the revolution of July 1830, in which he was wounded, gave the throne to Louis-Philippe and power to the mercantile middle class. In 1830 Daumier learned and mastered the still new process of lithography and did anonymous work for publishers, including political cartoons.

On the 4th of November, 1830, the print publisher Aubert and his son-in-law Charles Philipon launched the anti-monarchist weekly called La Caricature, see Figure 1, which was followed by Le Charivari in December 1832 , see Figure 2. The gift of Daumier for political cartoons caught the attention of Philipon the liberal journalist, and Daumier

Figure 1. Faceplate of an issue of La Caricature

Figure 2. Faceplate of an issue of Le Charivari.

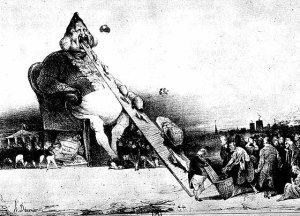

began contributing to La Caricature. He became a staff member of this journal. The journal Le Charivari was the first daily paper to be illustrated with lithographs. Thus Daumier, in the company of Republican artists, found a favourable milieu for developing his rigorous style and progressive ideas. The coonection with Philipon lasted 40 years with interruptions. The first interruption was due to the publication of Louis-Philippe as Gargantua (1832), see Figure 3.

Figure 3. Louis-Philippe as Gargantua (1832).

Daumier was imprisoned for 6 months for this work of lampoon of the bloated Louis-Philippe (1773-1850) who was shown as “Gargantua swallowing bags of gold extorted from the people.” (Chilvers, 1997). The journal La Caricature was also discontinued. In 1834 Philippon, in order to pay imposed fines, launched an even more vitriolic paper, the Association mensuelle. In its pages Daumier published lithographs that have all the power of paintings and are now considered among his masterpieces – for example Le Ventre legislative or The Legislative Belly; also Ne vous y frottez pas!; and Rue Transnonain, le 15 avril, 1834, see Figure 4. This lithograph depicts the brutal effects, a massacre of a family shot by government troops, during the repression that followed a riot. It was thus that the prints of his early career exposed the king’s corruption, hypocrisy and rampant greed as he rule in the interests of the newly risen bourgeoisie.

Figure 4. Rue Transnonain, le 15 avril, 1834.

Philipon provided a new field for Daumier’s activity when he founded Le Charivari, with the intent of holding up to good natured ridicule the foibles of society. In the last Daumier depicted the squalid aftermath of the massacre of working-class opponents of the government.

After the 1830’s Daumier’s style in lithography underwent a marked change. He was now drawing by sharp outlines than changed to line conceived as a web of sculptural contours, plus detailed modelling gave way to ever increasing selectivity of detail. This development may be traced from Le ventre Legislatif (1832) and La Rue Transnonian (1834) to the Robert Macaire series of the later 1830’s to the many series of the 1840’s and 1850’s ridiculing classical law and evils of the law courts. In the Robert Macaire series he lampooned the bourgeoisie in 100 lithographs depicting the adventures of the hero of a then popular melodrama. The total number comes to nearly 4000 (each in a large edition) and together form a parallel with Balzac’s conception of the Human Comedy. They comprise a various series of humorous scenes, composed with great care, giving a vivid and critical panorama of France’s social classes in transition. Also included are satires of the bourgeoisie – Les Gens de justice (1845-48), and public transport – Les Bons Bourgeois (1847-49).

The work of Daumier reflected developments in French society at the time of its greatest economic expansion between 1830 and 1870. Considered by the critics Theodore de Banville (1823-91) as early as 1852, Baudelaire in 1857, and Champfleury, as an artist worthy of comparison with Hogarth and Goya. Daumier’s life was entirely devoted to his work and can be divided into two parts. From 1830 to 1847 he was lithographer, cartoonist, and sculptor. Beginning in 1848 until 1871 he was an Impressionist whose art reflected in the lithographs he continued to produce. After 1833 Daumier was never again indicted even though his cartoons continued to attack the regime, the society, and the concept of life he scorned. At the same time he created many unforgettable characters. His types were universal – lawyers, businessmen, doctors, professionals, petit-bourgeois. His treatment of his lithographs was sculptural.

Daumier’s sculptures have not been significantly studies. He modelled about 15 or 50 small busts in clay for the window of the satirical journal where he worked. They had accentuation of detail that made them caricatures and constitute a gallery of the politicians of the July monarchy. Daumier was one of the first French artists to experiment with caricature sculpture. In 1832 he began a series of small grotesque busts of parliamentarians, for example Franco-Pierre-Guillaume Guizot, see Figure 5, and Alexandre-Simon Pataille, see Figure 6. Both of which are in the Musee D’Orsay.

Figure 5. Satirical bust of Guizot (1832-33).

Francois-Pierre-Guillaume Guizot (1787-1874) was a deputy minister and historian, and Alexandre-Simon Pataille was a member of parliament and magistrate. Daumier gave them

Figure 6. Satirical bust of Pataille (1832)

individuality and considerable satiric force by gross exaggeration of his victims most prominent features and characteristic expression. Among other important sculptures – first in clay, then to plaster, and eventually cast in bronze – was the bas-relief The Emigrants (1848-50) in the Musee d’Orsay, see Figure 7. Here he depicts a forlorn procession of

Figure 7. The Emigrants (1848-50).

un-individualised figures with grandeur and compassion. His statuette called Ratapoil (1851), see Figure 8, represents his archetype of the swaggering and corrupt thugs who had brought Louis-Napoleon to power. Honore de Balzac was one of the first to recognise Daumier’s genius as against his mere ability to entertain. Balzac, ironically, did not know

Figure 8. Ratapoil (1851).

Daumier as a painter and he once remarked that there was something of Michelangelo in Daumier. The point was well taken as it suggested Daumier’s dramatic power and his emphatic scale. Also his concern for the great passions even when the theme chosen might be trivial. Thus his interest in sculptural form was another link to Michelangelo, not only in his drawing but also his practice of making small clay reliefs and busts to help him visualise the 3-D shape. Cast into bronze after his death these sculptures became highly prized by collectors. Daumier’s caricature heads and figures are often spontaneous in style. In particular Ratapoil – skinned rat – embodied the sinister agents of the government of Louis-Philippe. A similar political type in his graphic art was Robert Macaire, see Figure 9, who was the personification of the unscrupulous profiteer and swindler. Daumier’s only close friends were sculptors, all of them poor, Romantic, and ardent left wingers.

Figure 9. Robert Macaire

From 1848 Daumier attempted to establish himself as a serious painter in oils. This was hampered by his fame as a left-wing cartoonist. Added to this was his dependence on fellow artists for subjects and his refusal to give his works the finish considered necessary. There were few oils before 1850 and none were characteristic. Most paintings were done between 1855 and 1870 when his connection with Le Charivari was interrupted for long periods. None of his paintings, as far as is known, were done on commission. His paintings, however, were inspired with much animation and built on a framework of very expressive drawing. Daumier’s brush handled the colour with such vigour that their vital force is astounding. Daumier, remained an ideologically committed artist whose non-academic training made hi remain a consummate artisan outsider amongst middle-strata and petty-bourgeois artists of his time – indeed he always stressed ‘…that one must be of one’s time!’

His paintings for the most part done after 1860 and were accepted four times by the Salon, but never exhibited otherwise. They remained, therefore, practically unknown up to the time of a collective exhibition at Durand-Ruel’s gallery in 1878. His painting is in the main a documentation of contemporary life and manners with satirical overtones – but some also feature Don Quixote as a larger than life hero. Thus in his sketches and oil paintings of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza he created a great modern reinterpretation of Cervantes, see Figure 10.

Figure 10. Don Quixote (1868).

Probably self-taught Daumier painted for his own pleasure from 1834. From 1847 these isolated attempts gave way to copies of Millet and Rubens and interpretations of his lithographic scenes, for example genre scenes, bathers, and lawyers such as Three Lawyers in Conversation, see Figure 11, now in Washington. He did execute commissions

Figure 11. Three Lawyers in Conversation (1855-57).

from the State for some religious paintings, for example Mary Magdalen in the Desert (1852), see Figure 12, and also We Want Barabbas (1853-59), see Figure 13. In the

Figure 12 Mary Magdalen in the Desert (1852).

Figure 13. We Want Barabbas (1850)

Salon of 1849 he exhibited Miller, his Son and the Ass , see Figure 14, and now in Glasgow, and in 1850 his Two Nymphs Pursued by Satyrs, see Figure 15, and now in

Figure 14. Miller, his Son and the Ass (1849).

Figure 15. Two Nymphs Pursued by Satyrs (1850).

Montreal. In 1851 he exhibited Don Quixote Going to the Wedding of Gamacho, and now in Boston. Apart from an exhibit in 1861 and the exhibition organised by his friends to help him financially, in 1878, just before he died, most of his paintings were unknown to the public and thus remained in his studio until his death. The exhibition was organised by the dealer Durand-Ruel and Daumier’s painter friends Corot and Daubigny.

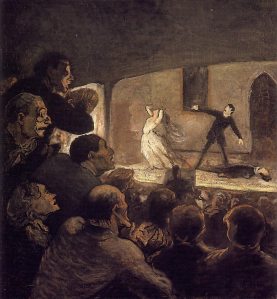

Daumier’s paintings, including over 300 oils and numerous watercolours, gained widespread recognition. The brushwork is usually rapid and vigorous. In subject he sometimes reverted to observations of daily life, for example his The Third Class Railway Carriage (1864), see Figure 16. A much earlier oil painting was The Theatre see Figure 17. Or

Figure 16. The Second Class Railway Carriage (1864).

Figure 17. The Theatre or The Melodrama (1856-1860).

he drew on mythology , for example his The Drunkeness of Silenus (1863), see Figure 18,which is not an oil work. or literature, including numerous works featuring Don Quixote.

Figure 18. The Drunkeness of Silenus (1863).

Daumier did not prime his canvases, they are often unfinished, and retain a sketch-like appearance. This gives a strong effect of spontaneity. Daumier’s paintings are highly original both in style and subject. He created the painting of morals and manners – la peinture de moeurs – and he shows everyday life around him, He transposed into his painting what had belonged to the domain of his caricatures of morals and manners.

Daumier, earlier than others, discovered Impressionism, with faces and bodies devoured by the surrounding light and becoming one with the atmosphere. He was indeed the first of the Impressionists. As early as 18148 his lithographs show contrasts effaced by light. The Impressionist lithographs are not numerous, but his paintings show that he was won over to Impressionism. His paintings assign him his time place in the history his time place in the history of the art of Impressionism – before Manet and Monet, both of whom admired him greatly.

Daumier was not often inspired by the subject of religion, but mythology excited him during his Rubens period under Lenoir. On several occasions he painted historical subjects – including Camille Desmoulins, the revolutionary leader rousing the crowd in 1789, see Figure 19. His Emigrants (1857) is an allusion to the authoritarianism of Napoleon III.

Figure 19. Camille Desmoulins, 1789 (1848-49).

Among his masterpieces in oil are Crispin and Scapin (1858-60), see Figure 20, and now in Paris, The Theatre or The Melodrama (1856), now in Munich, his Don Quixote and Sancho Panza (1868), which is now in Los Angeles, and The Third Class Railway Carriage (1864), now in New York.

Figure 20. Crispin and Scapin (1858-1860).

The directness of vision, lack of sentimentality, was what he used to depict current social life. This places Daumier in the Realist School of whom Courbet was the chief representative. Since his death Daumier has been recognised as a pioneer, chiefly of expressionism, as in The Painter before his Easel (1870), see Figure 21.

Figure 21. The Painter before his Easel (1870).

In 1871 Daumier, having refused the Legion of Honour, joined the Paris Commune. After 1871, now almost blind, he lived on until 1879. He died in Valmondois on the 10th or 11th of February, 1879. Daumier never made a commercial success of art but was appreciated by the discriminating and numbered among his friends Delacroix, Corot, Baudelaire, Michelet, Balzac, and Degas. They among artists collected his work. Daumier’s art so gained in luminosity and synthetic power. Through the work of his late period he came to be seen as the forerunner of Impressionism and in particular of Cezanne. Daumier’s importance was also recognised by Baudelaire. His subject matter was modern and urban which lumped him together the Realists. His art has many qualities of modernity with its generalised, un-idealised style. He also interacted with major 19th century politics – the revolutions of 1830 and 1848, and the Paris Commune of 1870-1871. He developed Romantic sculpture which was also urban, Realist, and political. Daumier was heir to Gillray, Hogarth, Gericault and Goya – though he was more naturalistic and less fantastic then Goya. Daumier never lost his consciousness of the working class and very rarely lampooned his own. Neither did he patronise the common people. His art was founded solidly on the truthful depiction as the result of acute observation of the faces, looks, dress and posture of ordinary people with honesty and compassion.

Sources consulted

Chilvers, I. et al. eds (1997). Oxford Dictionary of Art. OUP, Oxford.

Levey, M. (1974). A History of Western Art. Thames & Hudson, London.

Levey, M. (1994). From Giotto to Cezanne. Thames & Hudson, London.

Lucie-Smith, E. (1971). A Concise History of French Painting. Thames & Hudson, London.

Newton, E. (1956). European Painting and Sculpture. Pelican, Harmondsworth.

Vaughn, W. (1994). Romanticism and Art. Thames & Hudson, London.

Pingback: Printmaking and newspapers, New York exhibition | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: “Lawyer’s Library” – Daumier’s Law – Law and Lawyer Art – The Barristers House

Pingback: Lawya Art – ‘Lawyer’s Library’ – Daumier’s Legal Art – The Barristers House

Hello I believe I have one of Daumier art pieces. “A Quarrel of Allemano”.

Je suis à la recherche d’une recette de craquelins de pulpe à faire au four depuis deux semaines!! Aurais-tu un lien que tu pourrais partager? 🙂 Ou juste le nom d’un forum? Merci d’avance Julie!!!

bijoux bulgari prix replique http://www.aluxury.nl/fr/

Hello I have came across some Daumier art I have 12 original lighgraghs I want to no more about them if any one would be willing to

Mabey tellee how to tell if they are real ones and it has a little booklet saying they are lithograph any help would be helpfull