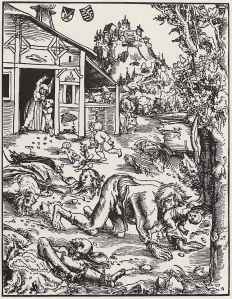

Woodcut of a werewolf attack (1512). Lucas Cranach the Elder.

1. Introduction

The werewolf is a creature of folklore and legend commonly referred to as a ‘man-wolf’ or ‘wolf-man’. Medieval superstition describes them as individuals transformed, or who can transform at will, into a wolf. In France the creature is called a loup-garou. Werewolves are all termed lycanthropes from the Greek lucos meaning wolf and anthropos meaning man. In folklore and myth a werewolf is a human who possesses the ability, or potential to shape-shift into a wolf or other anthropomorphic creature. The change is either on purpose or due to being bitten, scratched and thus infected, by a werewolf. In addition the transformation can be initiated by a sorcerer or witch. The full moon is often implicated with the change into a werewolf which, as an aspect of European belief, has spread worldwide. The belief in werewolves is therefore the belief in the human capacity to metamorphose into animal form – in this case a wolf (Fahy, 1988).

2. Etymology

The belief in werewolves is not just a European phenomenon but is encountered world wide. This is apparent when considering the etymology of the word. Medieval Europe held strong beliefs in the existence of werewolves during the 15th to 17th centuries, which was reflected in the literature of the time. The term lycanthropy is derived from lycanthropos of ancient Greece meaning wolf plus man (Rose, 2000).

In Old English werewolf is derived from wer or were signifying man, and the word wulf for wolf. In Old Welsh there is gwir and Old Irish has tear where wild dog is used synonymously for wolf. Again, weri from Old English means to wear the skin of a wolf, perhaps ritually. The word is compounded from lyc from the Proto-Indo-European root wlkwo meaning wolf, hence the vira of Sansrit, and the vir of Latin. Counterparts of the English word werewolf are found in the Germanic form of wehr-wolf, a variation meaning man-wolf. A cognate is the Gothic word wair, the wer of Old High German. I France the derivation of loup-garou is from the loup for wolf.

A representation of the loup-garou.

In Eastern Europe the idea of the werewolf is related closely to the concept of the vampire, referred to in Serbia as the vukodlak. In Lithuania the werewolf is called vyras. The word vampire in Slavonic languages is vampire and the origin of the English term, with the Greek vrykolakas originating amongst the Serbs, with werewolf being wilkolak amongst the Poles. For the Scandinavians the Old Norse cognate is verr. Again, in Old Norse there is the vargulf, a wolf that kills large numbers of livestock, which connects with warg-wolf. The words warg, werg, and wera are cognate with the vargr of Old Norse. This refers to an outlaw being regarded as a wolf, a ulfhednar seen as a wolf-like berserker wearing wolf skins in battle.

3. History

During the 16th and 17th centuries in Europe there were a great number of trials of alleged werewolves. This was a feature of the outcome of witch-hunting. The image of fear and terror generated by the wolf, and subsequently the werewolf, increased the intensity of the popular delusions of the time. A time in the middle ages of famine, disaster, black death and plague fanned by superstition and religious dogma. Partly the fear was exacerbated by the resemblance of the wolf to the its domestic relative – the dog. Across France, Denmark, Germany and Scotland werewolves were supposedly identified because their eyebrows met in the middle, because they had pointed ears, a long index finger, hairy palms, and because of a loping way of walking. Indeed one conclusion opined that “…the descriptions of werewolves extant in legend and folklore corresponded to some manifestations of congenital erythropoeitic porphyria… (Illis, 1964), and that werewolves resulted from contact with porphyria sufferers. The fear generated trials of so-called werewolves increased in frequency during the late 16th century.

Werewolves in the European tradition were sometimes regarded as diseased, rather than possessed, which in the 14th century was called daemonium lupum or melancholia canina. It does seem that there was a sympathetic element in the literature and folklore of medieval Europe. A sympathetic attitude that may have had its roots in an archaic totemic echo in the form of sentimentality towards wolves (Russell, 1978). The fear of water or hydrophobia, known as a symptom of rabies, in medieval times was confused with possession by demons. Hydrophobia, as an indication of infection with rabies, is a common affliction of feral dogs and wolves. Rabies was a problem with dogs in ancient Mediterranean lands, and this may have contributed to the popular fear of dogs. However, wolf attacks on humans were only occasional until the 20th century in Europe. The belief that wolves were predators and shape-shifters was a projection into folklore. The wolf-month of Anglo-Saxon times was a referral to the January pack behaviour of hunting wolves.

The wolf was gradually exterminated in north-western Europe. The clearance started in England and proceeded to Wales and the Scottish lowlands by the 16th century, followed by Ireland and the Scottish highlands during the 18th century. Wolf extermination followed in Denmark and most of Germany during the 19th century, and by the mid-20th century the wolf had gone from France. A sympathetic reaction during the time of the werewolf and witch trials a number of writers described the experiences of witches as the hallucinations, which were transient wolf belief delusions, resulting from herb and potion use, or from ointments and herb salves.

4. Mythology

The fear of werewolves or lycanthropes have been recorded in European literature since Ancient Greece, however the vampire and the werewolf suggesting they “…were always exotic and rare but as man has separated from the natural environment…his mythical and religious inheritance is challenged…” (Fahy, 1988) one description telling of a close relationship between wolves living outside the city of Parnassus with the local inhabitants (Graves, 1958).

Werewolf mythology can be best understood by examination of the ancient Greek myths of the wolf-cult. The god Apollo, who was the son of a she-wolf, was born in Lycia (Summers, 1933). As a rationalisation of the wolf-god Apollo was worshipped at Athens in the shrine of the Lyceum. A wolf was sacrificed to Apollo at Argos, and the wolf was honoured by the Athenians. Legends of werewolves were known in the central Pelopponese, and at various sites in Arcadia, where the temple of Zeus Lyceus was on Mount Lyceus, with the wolf also worshipped at Delphi. If the wolf was the incarnation (Summers, 1933) of the deity then the legends of the Arcadian werewolf can be traced back to the practice of totemism (Russell, 1978) making it plausible that a shaman, priest, or priestess would be attired in a wolf-skin disguise. The roots from the ancient Greek, such as luk for wolf, have been grafted onto history as wolf-cults and werewolfism.

In Greek mythology the Pan-Hellenic deity Apollo is closely connected to the wolf. This, as later legends have striven to explain, implies that wolf-god worship of werewolf belief were used in ritual reverence to Apollo as part of the cult of the Arcadian Zeus (Summers, 1933). Moreover, Fenrir the wolf who killed Odin is embedded in Norse mythology. In Italy at Mount Soracte, modern Soratte, Apollo Soranus was worshipped by wolf-skin wearing Hirpi Sorani (wolves of Soranus). The Hirpi were members of the Wolf clan that was totemic in origin. In other words the Romans knew of lycanthropy and called lycanthropes by the name versipelles or ‘turn-skins’ (MaCulloch, 1915). It seems that ancient totemic wolf clans were accused of lycanthropy in later legends that attempted to explain poorly remembered ritual practices and beliefs. Similarly in Ireland the Book of Ballymote refers to the people of Ossory as descendants of the wolf who had the ability to transform 1nto wolves.

5. Folklore

European werewolves have many names but their folklore is not common in England, with wolves eradicated during the early middle ages. In Ireland they were known as faoladh or conriocht, in Greece as the lycanthropus, and the French loup-garou. East European names included oik in Albania, mardagayl in Armenia, and varkulak in Bulgaria. In Spain there was hombre lobo, for the Argentine there is lobizon, with the Mexican nagual. The Dutch refer to the woerwulf and the Italians had lupo mannero. The Serbians have their vulkodlaks and even in Haiti the je-rouges.

Many names that mean wolf or wolf-man are originally Indo-European and European clans and tribes. These names arose during the transition from gathering economies to hunting tribal societies and many underlie medieval superstitions concerning werewolves. Fictional werewolves, as portrayed in films, television, and stories, are often the victims of circumstances beyond their control, or they are just murderous villains. Contemporary preoccupations with “…vampire and werewolf myths are deeply…ingrained in the human psyche, and manifestations of these phenomena may continue to appear.” (Fahy, 1988).

The process of reversible transformation in animal metamorphism is termed repercussion. The word refers to the power of becoming a werewolf whereby the individual becomes a fearsome and predatory villain that devours recently deceased corpses. There are a number of means and reasons why a person turns into a werewolf in folktale and folklore. A distinction has to be made between voluntary and involuntary werewolfism or lycanthropy. The transformation may be blamed on the spells of malevolent magicians or sorcerers, especially men who became lycanthropes after incurring the anger of the devil. Medieval treatment or intervention, apart from ecclesiastical trial, torture and execution, included bloodletting, purges consisting of wormwood, bitter aloe, colocynth and vinegar, as well as sedation with opium (Surawicz, (1975).

Those who had been ex-communicated by the church were believed to turn into werewolves. Again, the allegiance with Satan was attributed to a craving for human flesh, as was the grand mal seizures of the epileptic, or the affliction of hypertrichosis. Voluntary transformation alluded to the wearing of wolf skins, or sleeping out under a full moon on a summer night. Perhaps a totemic survival found in Italy, France and Germany. The French for werewolf is loup-garou and refers to a person who transforms into a wolf at night and then devours animals and people. The loup-garou de cimitiere is the werewolf that digs up dead bodies. In Haiti the loup-garou is seen as a sorcerer who can metamorphose whilst in Trinidad the term is legarou.

References and sources consulted

Douglas, A. (1992). The Beast Within: A History of the Werewolf. Longmans, London.

Esler, R. (1948). Man Into Wolf. ASIN, USA

Fahy, T. Wessely, S. & David, A. (1988). Werewolves, Vampires and Cannibals. Med.Sci.Law. 28 (2).

Graves, R. (1958). The Greek Myths. Cassell, London.

Illis, L. (1964). On Porphyria and the Aetiology of Werewolves. Proc.Roy.Soc.Med. 57 (23-26).

Jackson, R. (1995). Witchcraft and the Occult. Quintet Publishing, Devizes.

Lecoteux, C. (2003). Witches, Werewolves, and fairies. Inner Traditions, Vermont.

Lopez B. (1978). Of Wolves and Men. Scribner Classics, New York.

MacCulloch, J. A. (1915). Lycanthropy. In: Hastings (1912-).

Hastings, J. (ed). (1915-). Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics, vols 1-12. Scribner, USA.

O’Donnell, E. (1912). Werewolves. Methuen, London.

Rose, C. (2000). Giants, Monsters & Dragons: An Encyclopaedia of Folklore, Legend and Myth. Norton, New York.

Surawicz, F. G. (1975). Lycanthropy Revisited. Canadian Psychiatric Association Journa. 20 (537-42).

Willis, R. & Davidson, H. E. (1997). World Mythology. Piaktus.

Woodward, I. (1979). The Werewolf Delusion. Paddington Press, New York.

Pingback: Cursed Werewolves #FolkloreThursday | Ronel the Mythmaker

I enjoyed this information, very nicely done. I just want to suggest a small correction…maybe a typo? Werewolf in Italian is uomo lupo, or lupo mannaro, not lupo mannero.

It might seem silly, but when I make mistakes or typos in English, I appreciate being corrected.

Thank you.

I very much appreciate wikipedia.

Reblogged this on Die Goldene Landschaft.

I don’t know if you still read any comments or even still have the blog. Hopefully you do. I am a writer and I am currently trying to research werewolves in both Italy and Norway. I have used some of the reference books you have cited but I am have a hard time finding werewolf stories specific to those locations.

I have found a few books on history and folklore for each country but I was hoping for something more werewolf specific. Or is that a pipe dream? Any help you can give would be greatly appreciated!

Pingback: Werewolves: History, Folklore and More » Úlfsvaettr Craftsman